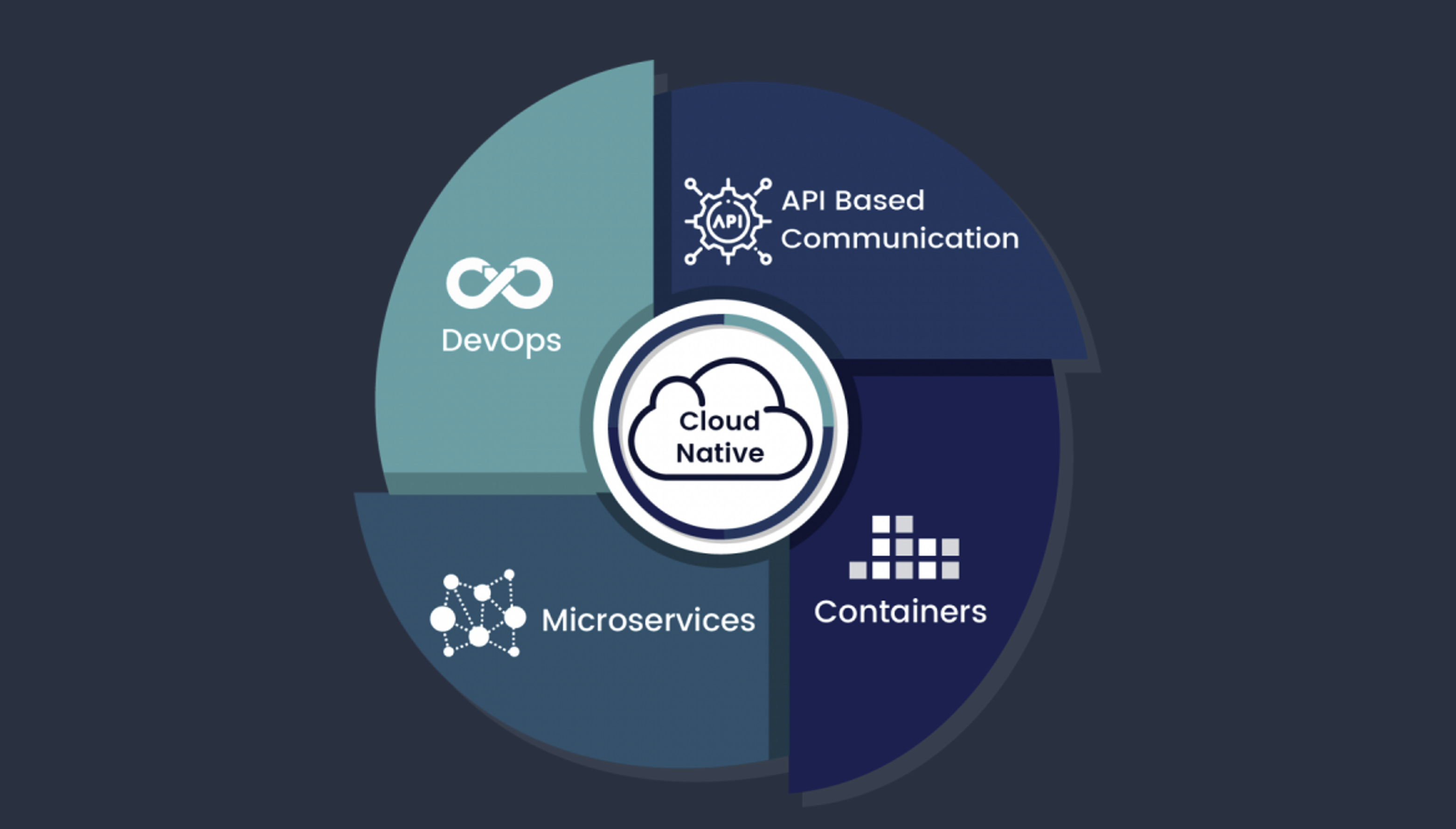

Introduction to Cloud-Native Technology

Brief introduction to Cloud-Native technology and how everything fits together.

Presentation of the setup

In this walkthrough, we will create an application that uses the main cloud-native components to illustrate their use in a cloud-native application development process.

This is the first first setup of our example that we will be using throughout the course, so if some concepts will be briefly introduced to get the tutorial up and running.

Containerizing apps

Install Docker

Containerizing your application, that is pachaging it and its dependencies into an executable container is a required step for adopting Cloud-Native. This will allow your applicatoin to run anywhere without needing to install those dependencies on the host machine.

The first step is to install Docker. Docker is distribued as a developer tool that is available for most platforms as Docker Desktop. You can check the link for platform spefic installations.

I have it already installed on my machine so I won’t go through the installation process here.

Running commands in Docker

To explore how docker works before we build our own application containers, we can bring up a containerized Linux shell in Docker, like so:

1

docker run -it ubuntu bash

This downloads the base ubuntu image, start a container, and run the bash command against it.

The -it parameters make it an interactive bash terminal.

This means that now, we are in the container and anything we run will happen in the container.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

apt-get update

apt-get install -y python3

python3

>>> print ("Hello Cloud-Native")

Hello Cloud-Native

>>> exit()

#

To leave the container, we type the command exit.

We just installed Python on the container without altering the local system.

To start the container again, we run docker ps -a to get the container ID.

Then, we start it with docker start $CONTAINER_ID to boot it, and docker attach $CONTAINER_ID$ to reconnect our shell:

1

2

3

4

5

docker ps -a

CONTAINER_ID=xxxxxxxxx

docker start $CONTAINER_ID

docker attach $CONTAINER_ID

exit

To clean up the list of stoped containers type the command docker system prune -a.

Building our own images

Now that we started a Linux container, installed Python and create a simple Python script that ran in the container, let’s say that we want to make this repeatable. We want to capture the configuration of the container (installing Python and our application) in our own container image. This simple example use only a simple Python script, however, you can imaging that the application can be anything you want it to be.

This process uses a configuration file known as Dockerfile.

It is a set of procedural instructions used to build your container like bash script that configure a VM with your app and its dependencies.

The only difference is that the output is a container image.

Create a basic Python app

Our app is a simple Python script:

1

print("Hello Cloud-Native")

We need to create a Dockerfile, pick a base container image to use as the starting point, configure Python, and add the program:

1

2

3

4

5

FROM ubuntu

RUN apt-get update

RUN apt-get install -y python3

COPY . /app

WORKDIR /app

Build the container and name (tag) it hello. Once built, we can the python script like so

1

2

3

docker build . -t hello

docker run hellp python3 hellp.py

Hello Cloud-Native

Here the command are the same like we just did before, here rather than starting from ubuntu container image directly, we use it as our base image for the Dockerfile. Then we run the same apt-get commands in the container.

Now, we encapsulated the environment we built and our script into a package that we can use and run ourselves or share with others.

Compare this to installing Python on your developer machine and running everything locally. For python, this might not be a problem, but imagine a more complicated application with several tools and libraries requiring specific versions and dependencies.

Containers solve this problem by isolating applications along with their dependencies in their own container images.

Adding a default command

The command executed in the container python3 hello.py is the same each time. Rather than repeating it each time, we can specify that in the Dockerfile:

1

2

...

CMD python3 hello.py

This command doesn’t change the way the container is built, it only specify the default command that will be executed when you call docker run.

This doesn’t stop you from overriding it and executing a different command at run time.

Adding dependencies

Most applications will need their dependencies to be installed on the base image. To do so, you install dependencies during the container build process. The same way we added Python on ubuntu base image before, we can install all dependencies needed by running commands on the base image:

1

2

3

4

5

FROM python:3

RUN apt-get update

RUN apt-get install -y mariadb-client COPY . /app

WORKDIR /app

CMD python3 hello.py

Here we start from a more specific base image that contain everything needed to run Python programs, updated it and installed the mariadb-client on it as an additional dependency.

Running containers on Kubernetes

Now that we have our application containerized, we need a kubernetes cluster to deploy our application the Cloud-Native way. For very simple deployments, we can deploy one container per VM and scale our VMs as needed. That way, we have the advantage of containers such as convinient packaging without the complexity of having a Kubernetes cluster.

However, you most likely will have a number of different services to deploy, so we need something more flexible. This is where a container orchestrator such as Kubernetes becomes handy. It contains all the tooling that handle the scheduling and monitoring of different containers on different machines.

With an orchestrator such as Kubernetes, we can adopt the microservices patterns where various parts of your application are deployed and managed separately.

We will see this in more details later in the course. For now, lets get us a running Kubernetes cluster to deploy our freshly built container.

Creating a cluster

Minikube is a great choice for testing locally and allows you to test with a multinode environment. It is maintained by the open source Kubernetes community. Follow the link https://minikube.sigs .k8s.io/docs/start/ to install Minikube for your system.

1

2

minikube start --nodes 2

kubectl get nodes

The start command will automatically configure kubectl to use Minikube context. In other words, any kubectl command will operate on the Minikube cluster.

Uploading your container

Up until now, the container we have created have been stored and run locally on your machine. Before you can deploy the container into Kubernetes, you will need to upload your container image data and provide a way for Kubernetes to fetch the image.

For this, we use what we call a container registery. Docker Hub is a popular choice as a container registery, particularly when it comes to public container images. You will need a Docker Hub account to start uploading images to the registery. Go to the Docker Hub website and create a free account.

Once the repository is setup, Docker is authenticated and your image is tagged, you can push the image to the repository with:

1

docker push $IMAGE_TAG

Deploying to Kubernetes

With our cluster ready and kubectl configured for us, we can deploy our first application.

For this, we need a deployment object that Kubernetes will create from a declarative configuration.

This means that you declare the specification wanted, like ‘I need 2 copies of my python application running in the cluster’ and Kubernetes will strive to meet the requirement you specified.

We will dive deeper into Kubernetes core concept in the next chapter. For now, here is the deployment code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: hello

spec:

replicas: 2

selector:

matchLabels:

pod: hello-cloud-native

template:

metadata:

labels:

pod: hello-cloud-native-pod

spec:

containers:

- name: hello-container

image: docker.io/aminrj/hello:1

This manifest will create two replicas of our python application after we run the kubectl create -f deploy.yaml command.

To check the result, we run kubectl get deploy command.

To see the pods created for this deployement we type kubectl get pods.

This is it, we created our first container, build the image, uploaded it to the registery and deployed it on our local kubernetes cluster as a deployement.

In the next section of the course, we will dive deeper into the core concepts of Kubernetes to learn how Kubernetes makes cloud-native application deployements more flexible.